Circus Maximus vs. Colosseum

For the Ancient Romans, there was no contest

(Diesen Text auf Deutsch lesen)

In 2008, The Independent published a story entitled “After 1,500 years as a ruin, gladiators’ stadium to be restored”. There the author describes how, at a now-derelict site in Rome, “gladiators and wild animals fought in mortal combat, and the central arena was often flooded so miniature triremes could battle it out for the Romans’ delight”. That the story concerned the plans of the Soprintendenza Archeologica di Roma (the archaeological arm of the Italian Ministry for Cultural Heritage and Tourism) to restore the site of the Circus Maximus— not the Colosseum—reflects a humorous, if persistent, irony: the Circus Maximus may have held the greatest audience of any spectacle in ancient Rome, but it is only when repackaged as a “gladiators’ stadium” today that it can compete for some share of the contemporary imagination.

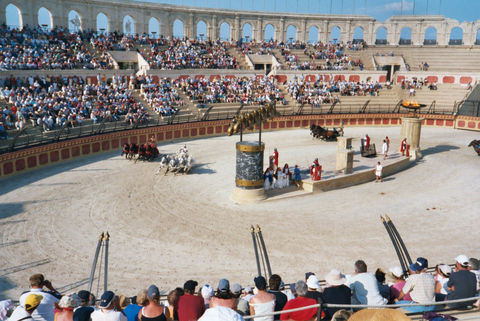

And yet, the reality in antiquity was the opposite of our expectations today. For among the many misperceptions about the Roman games that have become widespread, especially as a result of popular film and television, is the belief that gladiatorial games were the premiere spectacle at Rome: for instance, it is often supposed that they attracted the biggest audiences or the most partisan fans. In fact, neither assumption is true. The Circus Maximus was many centuries older and considerably larger than the Colosseum. Chariot races draw the largest crowds in Rome and throughout the empire and continued to do so centuries after the gladiatorial games fade away. Furthermore, there is no evidence for spectators in arenas behaving as fanatically as those in circuses or even theaters.

What was the appeal of the races in the circus? A day there could be hot, noisy, and dirty, but it held out many attractions besides the thrill of the races themselves and their accompanying spectacles. While the glare of the sun mad it hard to see, the roar of the crowd mad it hard to hear, both problems that the signaling system of trumpets and lap counters on the euripus (the central dividing barrier) somewhat alleviated. Seats at the circus, which are described as narrow, hard, and dirty, could add to the discomfort. However, because “the law of the place” allowed men and women to sit beside one another, the circus held out the promise of a chance romantic encounter that sexually segregated seating at the theater and amphitheater forbade (Ovid The Art of Love 1.142). Ovid counsels his readers to exploit their cramped quarters to pick up attractive female spectators (1.135 ff.; cf. Amores 3.2).

Opportunity and chance also lie behind the other major attractions of the races: prizes, betting, and curses. Nero and Hadrian, among others, staged imperial “giveaways” in which tiny inscribed balls were thrown into the stands and the audience members who caught them could claim prizes such as food, clothing, and animals (Cassius Dio 62.18.2; 69.8.2). Placing wagers was rife (Tertullian On the Spectacles 16.1; Martial Epigrams 11.1.15) and the outcome of such risk-taking, whether positive or negative, could be swift and emotional: one commoner fainted in the stands after the horse he bet on made a come-from-behind victory (Epictetus 1.11.27), while a praetor allegedly lost his fortune betting at the very games he organized (Juvenal, Satires 11, 194–96). Juvenal captures all of these elements of the experience – the heat, the noise, the betting, and the crowd’s topsy-turvy state – when he grouses about the circus clamor that interrupts his dinner party (Satires 11.193).

When taken as a collective, these literary sources and the preserved visual and material culture (e.g., fan memorabilia, domestic decoration, funerary monuments) demonstrate that the circus games were much more than public, ceremonial occasions. Rather, they were events that could play a significant role in the way that Romans at all levels of society structured their private experience, both inside and outside the arena. To be sure, a chief attraction of attending the games was their edge-of-your-seat, high-speed spectacle: the opportunity to witness a favorite faction, charioteer, or horse prevail while risking life and limb and, at the same time, to watch rivals suffer spectacular crashes in defeat. And yet for many spectators, race days might also entail thrilling moments of personal revelation – of winning a prize or a bet, of discovering a lover in the stands, of seeing a curse fulfilled, of finding salvation in a hero or losing all hope witnessing his death. Romans came to the circus not only to live in the hyper-charged present, to see and be seen within the collective hive, but also to imagine an escape from their own mundane lives, perhaps even to alter their fates. The potential for such moments of revelation, set against the backdrop of high drama, undoubtedly explains why – hundreds of years after he wrote them – Juvenal’s words still rang true: “all Rome today is in the Circus” (Satires 11.197).

Sinclair Bell, 6. Oktober 2017

Sinclair Bell is Associate Professor of Art History at Northern Illinois University.

Further reading on this topic:

Sinclair Bell & Carolyn Willekes, “Horse Racing and Chariot Racing.” In The Oxford Handbook of Animals in Classical Thought and Life, edited by G. Campbell, 478–90. Oxford: Oxford University Press 2014.

Sinclair Bell, “Roman Chariot-Racing: Charioteers, Factions, Spectators.” In Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Sport and Spectacle in Greek and Roman Antiquity, edited by P. Christesen and D. Kyle, 492–504. Malden, Mass.: Wiley-Blackwell 2014.