Greek Horse Races, Politics, and Identity

(Diesen Text auf Deutsch lesen)

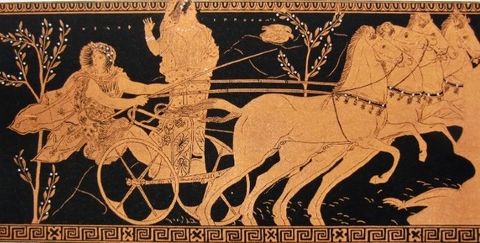

Everything was different at the Olympic Games of AD 67: they were held two years too late, musical contests had been added to the programme, and the victor was known before the competition had even started. The initiator of these changes was the man who saw himself as the most versatile athlete of the ancient world: the emperor Nero. According to our sources, he had become a little too ambitious in one discipline, though: his attempt to drive a ten-horse-chariot failed and he fell off the chariot much to the hidden amusement of the spectators.

In many ways the games of AD 67 were exceptional, and after Nero’s death, they were annulled and deleted from the victor lists. One aspect was not exceptional at all, however: the participation of prominent people in the horse races. For the hippic events, the Olympic victor lists read like a ‘who is who’ of Greek history.

Unlike Nero, however, most of these prominent participants would not have take the risk to make themselves a laughing-stock by personally driving their chariots. Success in the races mainly required investing a considerable amount of money: these race horses were not just proud animals, but expensive prestige objects. As such, part of their raison d’être simply was to demonstrate that their owners could afford them. So for many very rich people like Sicilian tyrants, Thessalian aristocrats or members of the incredibly wealthy dynasty of the Ptolemies who ruled over Egypt it simply was no question whether they should compete or not. Others, however, were more hesitant. So why did Greek elites engage in horse races?

Let’s begin with a possible, but most certainly incomplete answer: it was all about the race and the horses. The first thing we have to bear in mind here is that the perspective which matters most in ancient Greek horse races is not the perspective of the actual participants in the competition, the charioteers or jockeys, but that of the owners of the horses. They were the ones listed as victors, and we simply know next to nothing about the charioteers and jockeys.

The owners were proud of their horses and emphasized when they stemmed from their own breeding. Some even steered the chariots themselves. Yet the mere fact that horse owners were not necessarily present at the games in which their horses won victory (the locus classicus is Plut. Al. 3), suggests that some of the most important aspects of equestrian competition did not happen on the day of the race itself but after the contest. A true passion for equestrian competition may thus not have been the major driving force behind all of these agonistic activities. It was rather about winning, and maybe not even about winning itself, but about the celebration of the victory, since agonistic success gave enormous prestige and could be used to achieve and secure political power or to enforce a political argument.

To give an analogy from modern football, the club slogan of a well-known sports club from North Rhine-Westphalia which is “Echte Liebe” (“true love”) did not correspond to the mindset of Greek horse owners. For them, it was more about what the magazine of a rivalling and even more famous football club labeled in response as “Echte Spitze” (“truly at the top”). In order to be celebrated, you needed to win, not to be passionate.

Horse owners wanted to demonstrate that they were better (wealthier, more successful etc.) than their competitors. The essential components of agonistic poetry commissioned and written to perpetuate successes in this discipline included the place of victory, the discipline and the name of the victorious horse-owner, all other information was optional. It was surely possible to praise a victor “who delights in horses” (Pind. Ol. 1.23). Yet, even in such a case the emphasis was not on the passion for the animals, but on the close relationship between the owner and his objects of prestige.

So it comes as no surprise that successful charioteers did not reach the status of rich stars in Greek horse races. The horse owners monopolized the commemoration of the victory. They took center stage and had no need for any equivalent of the racing stables of the Roman circus factions. Greek horse owners used their victory celebrations for their own self-presentation and made good use of the symbolic capital inherent in the victory. Depending on what was useful for them in the political discourse of the day, they had poets to present a fitting image of their victory. Part of this image was an adequate social and political identity.

Horse races were not just a typical elite hobby like hunting. They had a competitive character and winning was key. This is why an often-quoted modern definition for “game” which is sometimes applied to sport does not hold true for Greek athletics, at least not for horse races. This definition specifies a “game” as “the voluntary effort to overcome unnecessary obstacles” (Bernard Suits), which lacks an essential component Greek sport: the element of competition (and winning).

To put it in a nutshell, there definitely was more than one possible reason for a Greek ruler or aristocrat to compete in horse races. A necessary prerequisite, though, was wealth – apart from the high cost of purchasing horses, the logistical operation to make it to the races was far from cheap too (see Sandra Zipprich’s contribution). Yet, some members of Greek elites were just happy with their parade horses or never engaged in horse breeding at all. So, the political usefulness of a possible agonistic victory was key. Competing in horse races was not simply the obvious thing to do. Neither was a passion for horses and horse races the decisive factor. Galloping horses in Greek sports were all about politics and identity.

Sebastian Scharff, 29. September 2017

Sebastian Scharff is a Postdoctoral scholar at the Department of Ancient History in the University of Mannheim.

For more on this topic:

Decker, W., Sport in der griechischen Antike. Vom minoischen Wettkampf bis zu den Olympischen Spielen, Hildesheim ²2012, 86–94.

Moretti, J.-C. & P. Valavanis (eds.), Hippodromes and Horse Races in Ancient Greece, forthcoming.

[see https://books.openedition.org/efa/6382]

Petermandl, W., Olympischer Pferdesport im Altertum. Die schriftlichen Quellen, Kassel 2013.

Platte, R., Equine Poetics, Washington, DC, 2017.